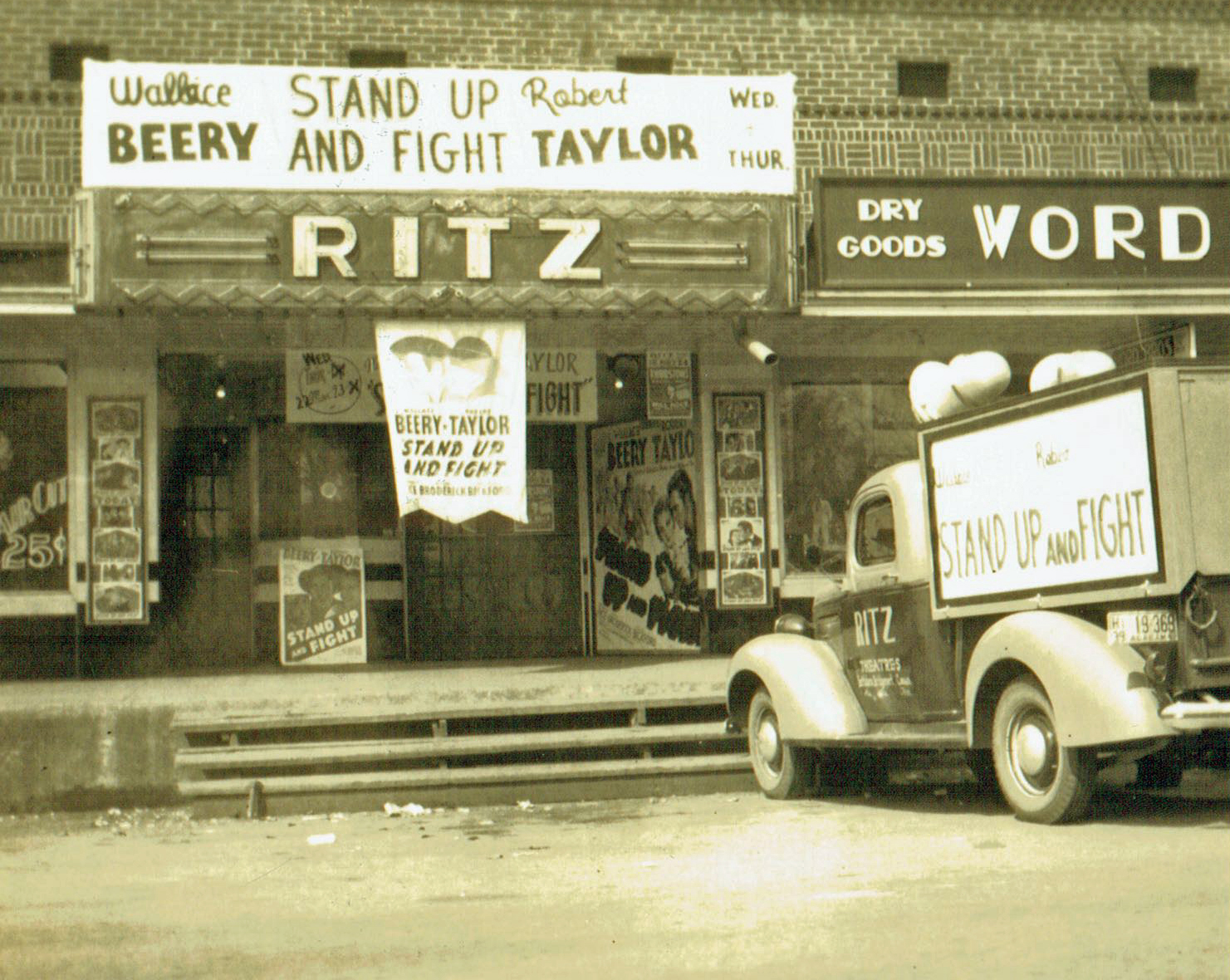

Built in 1932-32 as part of the Word Block, the Ritz Theater was located at 216 South Broad and opened for its first show in 1936. It offered both stage shows and movies. It is one story brick building.

The Ritz opened in 1936 and closed in 1972. It was not Robert Word’s first foray into movie theaters. Word showed movies in a large tent prior to opening the Ritz called the Airdome. Reuben Miller writes about this and the technology of the Ritz in his story below, from the 2002 Jackson County Chronicles.

After the Ritz closed, Southern All-Sports opened in this space and is found in the 1972 city directory. This business is still in this space. Owner Dean Guthrie provided a tour of the old Ritz lobby in the photos below.

Current view: Southern Allsports Main (Center) Building

1939 Ritz photo captured from Bob Word’s movie

January, 1939, the date this movie opened

Ritz during World War II

1948: Beulah Jacobs on the square

1949: Three guys in front of the Ritz

Paul Machen provided this photo of the Ritz. The three men are unidentified. The movie “The Doctor and the Girl” opened in 1949 and starred Glenn Ford, Charles Coburn, Gloria de Haven, and Janet Lee.

Remains of the Ritz

Though the marquis is long gone, the infrastructure for the Ritz still remains.

Remains of the divider between black and white sections of the Ritz

The patches in the floor of Southern Allsports supported the divider between the white and black lines for the theater.

The double door for white patrons (left) and the single swinging door for black patrons, which still remains (right). Dean Guthrie, owner of Southern Allsported, shows the door where Black patrons entered and immediately took stairs up to the balcony.

To see the remainder of the Ritz, leave the square and exit the back door of Hammers. The back of the Ritz has been converted to a warehouse. It was used by a heating and air conditioning business who built a wooden floor over the slanted concrete floor of the theater, which is still found under the current wood floor. The walls, balcony, projection booth, and even the fringed red velvet curtain over the screen still remain. Here are photos of the remnants of the Ritz.

View of the entire theater from the top of the balcony stairs

Note the curtain remaining over the screen area.

View of the courthouse from the projection booth

View of the balcony

Looking toward the balcony from the floor

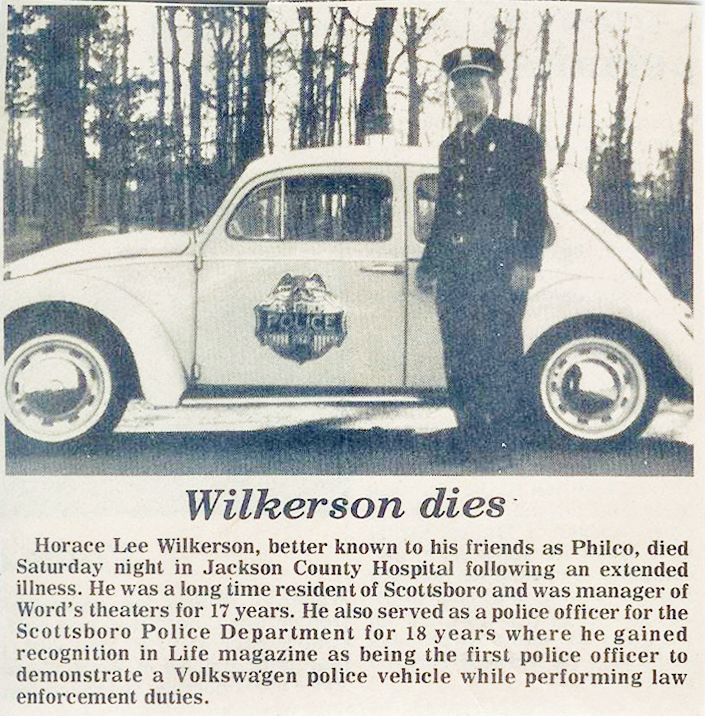

1984: Philco tribute from The Daily Sentinel on his death

Life Magazine ad featuring Philco in his Volkswagen police car

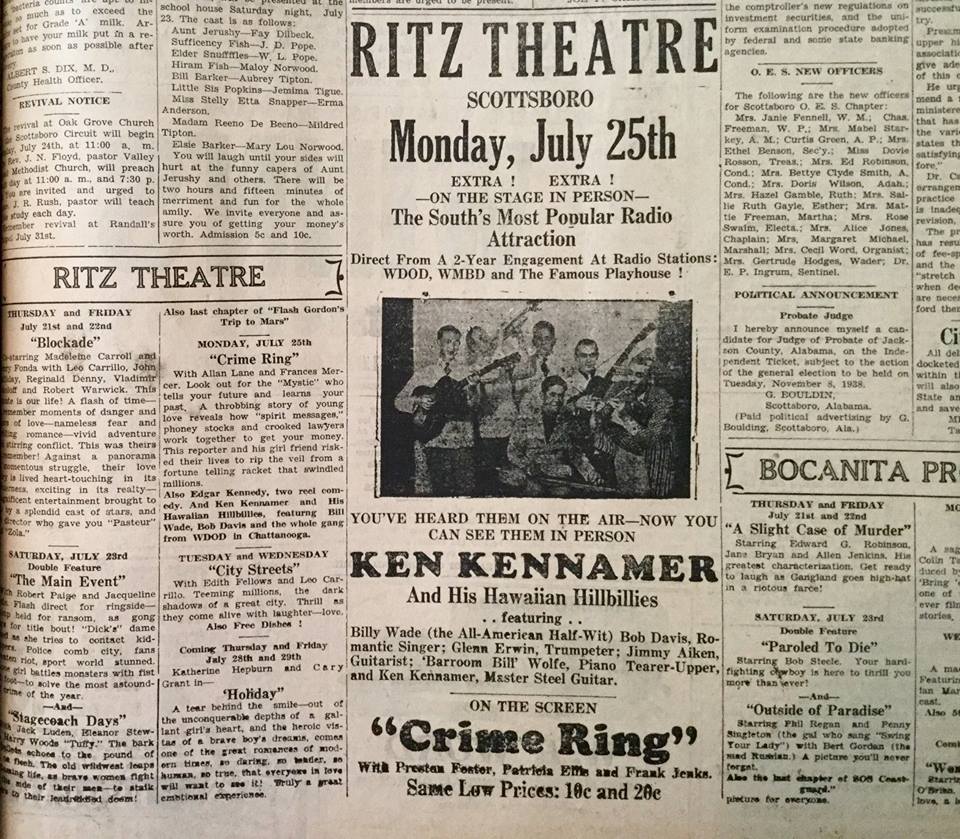

1942: Ritz ad from the Reminder featuring the lighted marquis

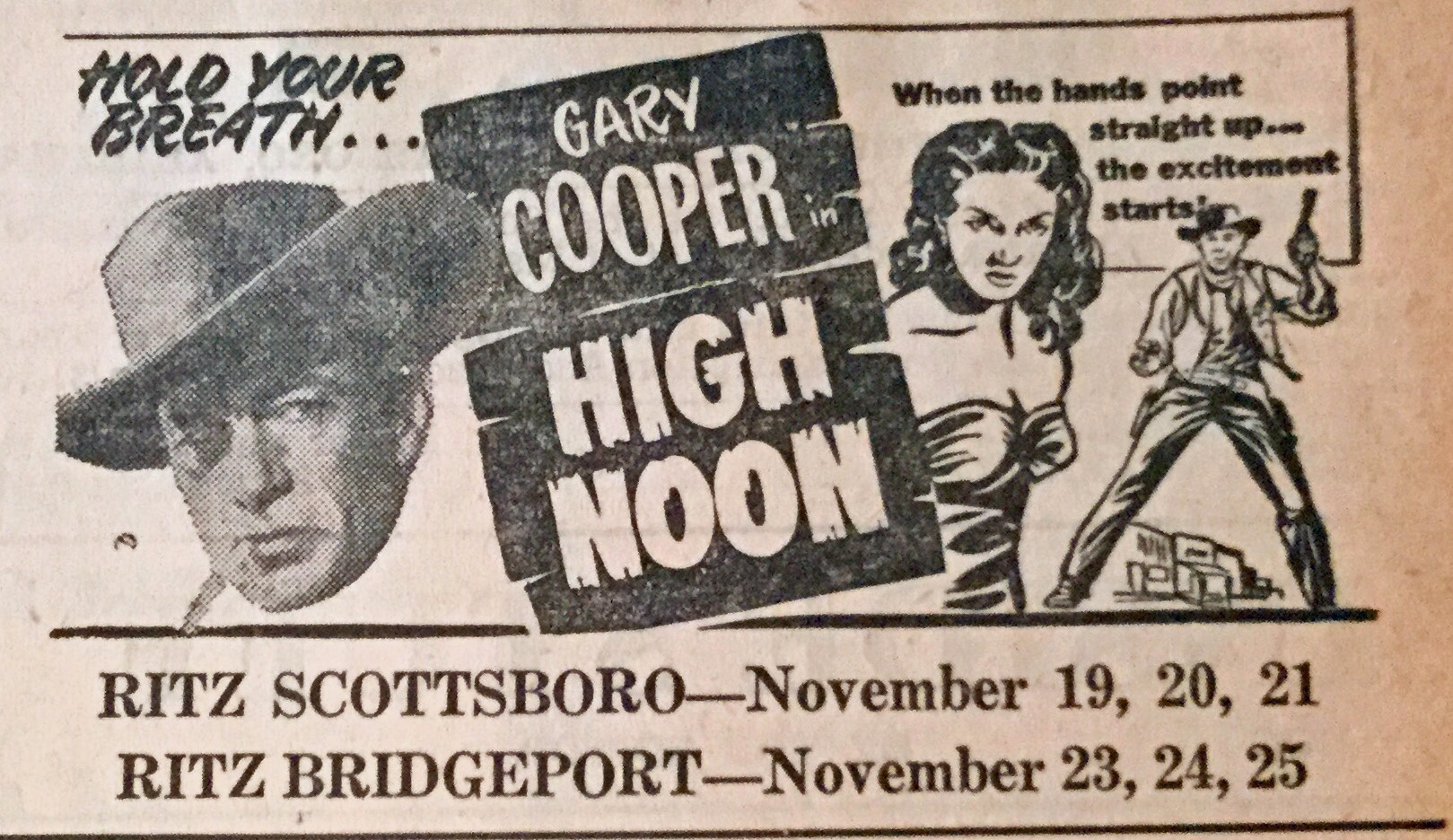

1952: Ritz ads from the Progressive Age

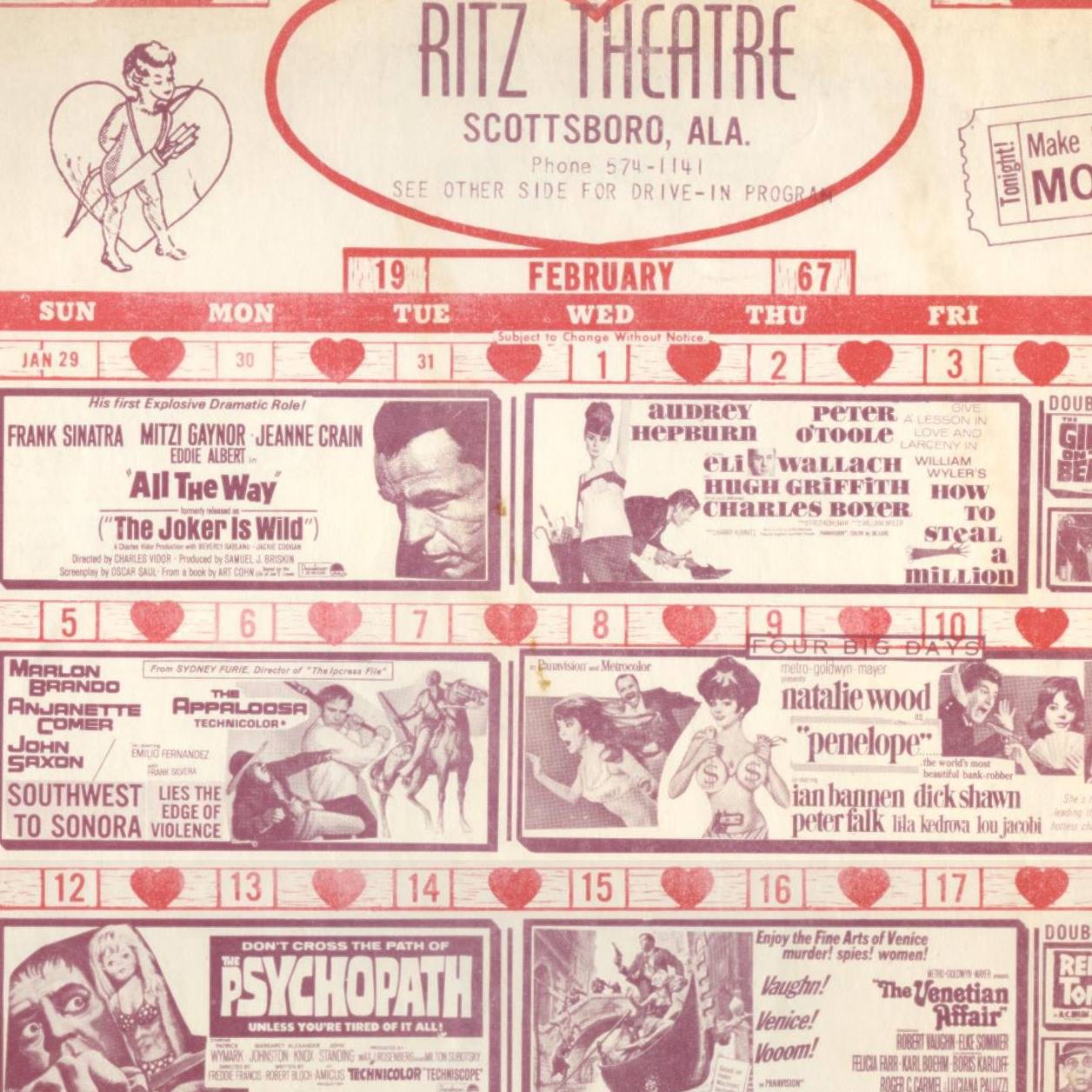

February 1967: Ritz ads

Marilyn Morris shared this bit of Ritz history on Facebook.

2002: Reuben Miller’s history of the Ritz from the Chronicles

THE STORY OF THE AIRDOME AND THE RITZ THEATRE by Reuben Miller

In 1935, Mr. William Jacob Word, Sr. was still holding the “paper” on a structure he had built for a Vaudeville group who went broke and were never to use their open air theatre. This theatre consisted of a stage with wings right and left,adequate footlights, and a set of tinseled curtains. All were sheltered from the weather by a roof above. The auditorium was bounded by a board fence ten to twelve feet high. This fence stood on the perimeter of a residential size building lot at the comer of Peachtree and South Houston Streets (where Ms. Mary Ellen Caulfield made her home in later years.)

Seating in this unique auditorium consisted of bleachers on each side from high on the walls to the floor which had a natural, auditorium-slope front to back. The floor was dirt, covered with wood shavings from Mr.Word’s lumber company planer. The center section had rows of folding, un-cushioned seats, leaving two aisles, right and left, rendering full access. Incidentally, the only shelter for the auditorium was the air and sky above. Yes, the air and the sky made loan of themselves for a name: AIRDOME. A better name could never have been chosen. Mr. Robert Word,son of Mr. Jake (as he was known far and wide), had been “after” his Dad to let him have this place for a movie theatre. Sometime early in1935, arrangements were made, and Robert got the Airdome.

A snow white sound (perforated) screen was installed near the back stage wall. The sound delivery system was behind the screen. Out front a projection booth was built and mounted on four power pole-like wood supports. Yes,there it was up on stems. The projectionist climbed a ladder to his work. Inside was a pair of rather ancient, but good, Powers projectors mounted on two CTR (CincinnatiTime Recording)system sound heads (the mechanical portion of sound-on-film reproduction.)

I never knew, but always assumed, that the electronics were CTR, also. The Airdrome had good sound, and even with the old Powers projectors the picture w a s clear, bright, and steady, steady as the stars in the dome above.

Yes,we watched the movies under the stars of the heaven. It was in the Airdome that we saw “WagonWheels” with Randolph Scott and Judith Allen, and featuring Billy Hill’s grand old song whose title was the same as the picture. “TailspinTommy”was a serial we saw with thrills in the air. The thriller, “Frankenstein,”was another feature which played the Airdome in the summer of 1935. “RoseMarie” with sweethearts, Nelson Eddy and Jeanette McDonald, played in 1936.

Mr. Robert Word told me a story of showing “Rose Marie”at the Airdome: It was late1936,and, as some readers may remember, the weather In Scottsboro, Alabama can be quite cruel to open air theatre. During one of the play dates of “Rose Marie” the weather became unsuitable for viewing open air movies. It began to rain, and the audience went home- except one lady and her husband. They were seated under their umbrella, seeing the movie to completion, all by themselves, all the way to “The End,” the management and employees wishing to close up and go home. In some cases the show had to be cancelled and played another night,with the audience in someway reimbursed.

Two summers 1935 and 1936….and then the Airdome, Powers projectors, sound screen, and CTR sound (“moom picher”) and all, moved to the west side of the square and became THE RITZ. Cale Brad Thomas’ Cafe became the lobby and box office. A building just completed adjoined at the back became the auditorium and the first air-conditioned building in Scottsboro. Cooling was accomplished by “washing” the air. The air washer was located outside, high on the southwest comer of the building. Excess water dripped to the ground. It later was known as a water fan still used in some southwestern states. Water is forced in front of a fan in a fine spray. Cooling happens due to evaporation.

Soon after the move, the old Powers were replaced by newer Simplexes, and the CTR was replaced by RCA. Performance was excellent! The dark lights at The Ritz were the brightest anywhere. We could easily find our seats.

In 1942, I was asked to go under the tutelage of a grand guy the whole town knew and loved, projectionist Raymond James. This came about due to several reasons: my Interest in radio (known by all because I had been heard on my own homemade radio stations), my other electronics gadgetry history, and I had been a “patron” for so many years. Plus, Mr. RobertWord’s brother, Hal, recommended me. In just four weeks, Raymond James went on vacation for a week....As I remember, everything went well, even though I did have a very short three and one-half minute reel to one of the features. That one kept me hopping!

My friend, who had honored me with an admission pass for so many years, then became my “boss man.” Things learned there were helpful all through my life,and I shall be eternally grateful. I served as a part-time projectionist until the spring of 1945when I went away to school and paid my room and board as, guess what, a projectionist at the Tiger Theatre.

It was in the Ritz that we laughed and cried to the antics of Mickey Rooney as “Andy Hardy”with Celia Parker as his sister; Lewis Stone as father, Judge Hardy; Faye Holden as the Mom; Sarah Hayden as the rental old maid aunt; and Ann Rutherford as Andy’s sweetheart, Polly Benedict. We saw Gable and Leigh in “Gone with the Wind.” Remember the Scottsboro movies when we saw ourselves and our town? We went into “the war years” with Robert Taylor and Vivian Leigh in the painfully beautiful, unforgettable “Waterloo Bridge.”

From Airdrome to the Ritz. Today,the Ritz lobby is home to Southern All- Sports. The theatre is gone but a host of movie fans still remember the first and last movie they viewed at the Ritz on Broad Street. Ah! What pleasant memories!

2015: Wes Mayberry’s story for The Daily Sentinel

On February 25, 2015, as part of the paper’s coverage of Black History Month, Wes Mayberry wrote the article below entitled “Remembering a segregated past”:

February is Black History Month, and several local African-Americans have stories to tell about growing up in Jackson County during a time of segregation. Local resident and retired teacher Tiajuana Cotton is one such individual. Cotton is currently writing a book focused on this subject matter, but to recognize Black History Month, she stopped by The Daily Sentinel on Monday to share her recollections on going to the movies and being an integrator.

The building that is now Southern All-Sports on the west side of the square in downtown Scottsboro used to house the Ritz, a one-screen movie theater with approximately 100 seats. The Ritz closed in the early 1970s, but Cotton recalls a time during her childhood in the early 1960s when she and her friends watched movies there.

“The theater was segregated, and we had to go there in groups. Since we were black, it was very dangerous to go alone,” Cotton said. “So we had to wait until a group of us could gather, and then we would go to the Ritz as a group.”

Cotton said this group of friends consisted of mostly school-aged kids ranging from age 7 to their early 20s. And once they arrived at the theater, they were forced to walk around to the side of the building to get their tickets.

“We weren’t allowed to walk up to the main ticket booth. That was for whites only,” Cotton said. “If any one of us was bold enough to go to the main ticket booth, we would not be sold a ticket.”

Cotton remembers the long rope that worked to segregate the theater between blacks and whites. And the places on the floor where the poles supporting these ropes once stood are still visible inside Southern All-Sports.

Once the African-American customers got their tickets, they had to walk up a very steep set of stairs in near pitch-black darkness, Cotton said. Blacks were banned from watching the movie downstairs with the white viewers, which made the concession machine inaccessible to African-Americans.

“The concession machine was on the white side of the rope, but we would occasionally find a white person kind enough to get concessions for us if we gave them the money,” Cotton said. “If we couldn’t find anybody, we would sometimes wait until about halfway through the movie to sneak across the rope and get our own concessions.”

And, out of frustration from the racial discrimination, the blacks would sometimes become devious and throw ice and popcorn down at the whites in the theater, Cotton said.

“I never did that myself, but I remember others doing it,” she said. “And by the time the movie was over, we knew we were in trouble because the whites were going to come after us. Most of the time, we had to run all the way home while being chased, but we knew we were safe once we crossed the railroad tracks. The whites that chased us would never cross the tracks for some reason.”

Moving from the topic of the theater to that of her schooling years, Cotton said she holds a special place in the history of Stevenson High School. Cotton and her sister, Bessfanette Stewart, along with two other African-American girls, Zata Bynum and VeEtta Cole, were the first to integrate SHS. And these girls got a scare during a pep rally that year.

“We were sitting in the stands at the football stadium during a school pep rally, and some students came toward us motioning for us to follow them,” Cotton said. “We were scared and didn’t know what to do, but we decided to follow the students, and we ended up in the middle of the football field in front of the entire student body. We were terrified and shaking. We thought we were about to be killed execution-style until we realized we were being inducted into the National Honor Society, which was one of the defining moments of my life.”

The National Honor Society, which was also known as the Beta Club at the time, was led by Mrs. Jan Britton at SHS, Cotton said. Britton took the club to Birmingham for a state convention and registered the students to stay at the Redmont Hotel.

“But Mrs. Britton was disappointed to learn that the hotel wasn’t integrated,” Cotton said. “She was devastated almost to the point of tears and didn’t know what to do because she knew she couldn’t leave us four black students out on the street. She must have pleaded and begged on our behalf because she was able to convince the hotel staff to let us stay there.”

And thus, after integrating their school, Cotton and her colleagues were the ones to integrate the Redmont Hotel. African-Americans had never before been permitted to stay in any of the large hotels in Birmingham, making this quartet the first to do so, Cotton said.

Cotton said she could tell dozens of stories concerning her upbringing in a segregated society in Jackson County but added that she’s saving several of them for her upcoming book. And while some remnants of segregation, such as the marks on the floor at Southern All-Sports, remain to this day, Cotton said much progress has been made since her days of going to the Ritz with her friends. “As a city and county, we have come a long way from the days of my childhood,” she said.

Tales of the Ritz

Brian and Dorothy [Heath] and Trethewy sent this memory of the Ritz. Brian worked part-time in the Ritz for five years.

My favorite Saturday was to go to the Ritz for cowboy movies. Philco maintained pretty tight control except when someone was able to start a Coke bottle rolling down the floor from the back of the main seating area to the front. I also remember the craze for going to the dime store to purchase a cheap, small metal squirt gun and a small bottle of the cheapest perfume – especially “Midnight in Paris” in the little blue bottles. Then, fill the squirt gun with the cheap perfume, sneak it into the show and try to catch somebody in the back of the head with a stinky squirt. Of course, I’m not sure if I actually had one of these “stink bombs” or only thought I should have had.

Warne Heath remembers, “I spent many Saturday afternoons and Friday nights in that place. Kids would become so loud and unruly that the manager would turn on the lights and walk out on the stage and threaten to throw everyone out if we didn't behave.”

Bob Hodges wrote in his “Going Home Again”: “There are long lines at the two downtown theaters: The Ritz, where Viola Hamlet would sell you a ticket on this Saturday for a double feature, including a western, a who-dunnit, and a serial episode. There were two rules rigidly enforced at the Ritz by Philco, who was every teenager’s substitute disciplinarian when away from home. You couldn’t put your feet on the back of the seat in front of you, and you couldn’t talk. It always was ironical to me that right in the middle of the who-dunnit, the only talking I could hear usually was Philco telling other people not to talk. Years later, after the Ritz closed, I thought it was fitting that Philco became a cop ‐- he had been in law enforcement in the theatre business for years.”

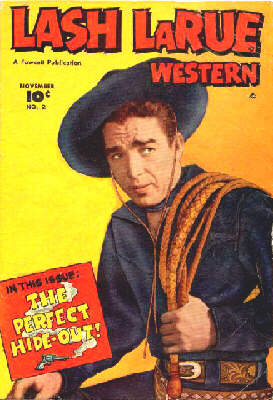

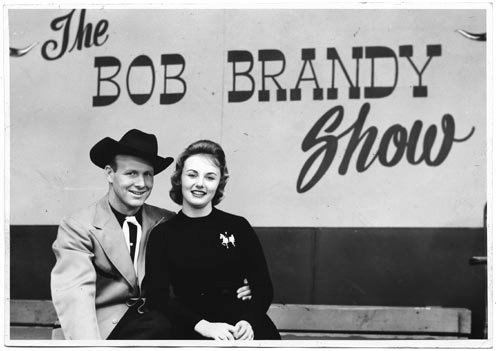

The crowd around the Bake Shop table on Saturday morning talked about the various stars who had made guest appearances at the Ritz: cowboy star Lash LaRue, Chattanooga TV personality Bob Brandy, and county singer Webb Pierce, whose 1959 Bonneville featured leather saddle seats, a pistol gear shift, derringer directional signals, and a dashboard inlaid with silver dollars.

David Bradford recalls that the manager, Philco, was a constant and menacing presence at The Ritz, patrolling the aisles to prevent rude boys (not him) from stomping paper cups on the floor to make them pop and blowing on empty Raisenette boxes to make them squeal (they had a cellophane pane that would vibrate like a reed). Philco’s name was Horace Lee Wilkerson. His home off Tupelo Pike doubled as his radio repair shop and a “Philco” sign (Philco was a brand of appliances) hung outside the home/shop. From that association, he derived his nickname.